At their national convention in 2012, Republicans mounted a clock counting the growing US national debt on the wall, a warning of the looming financial catastrophe

they said imperiled Americans.

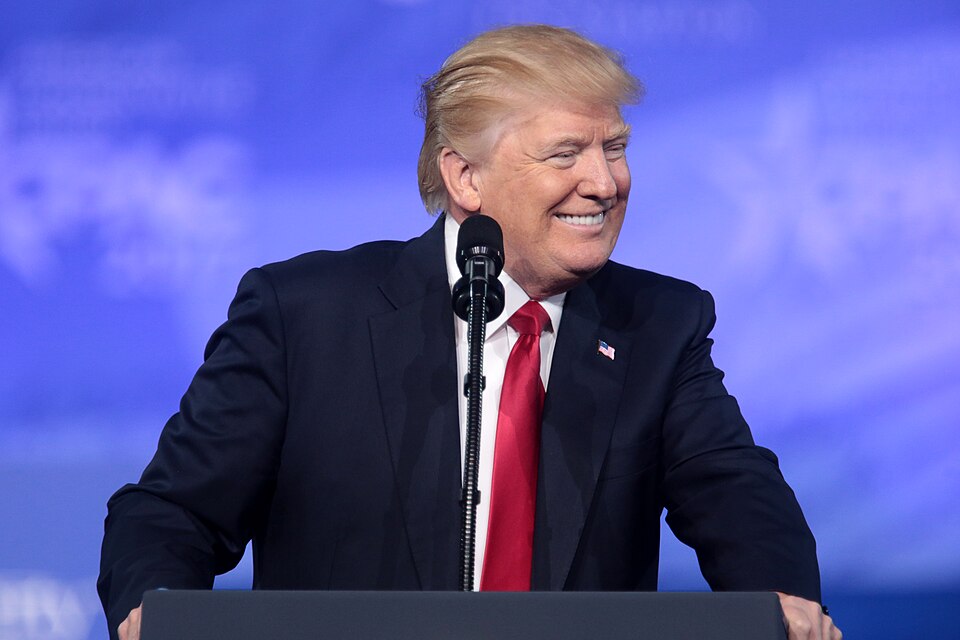

Eight years later, the clock has stopped under Republican President Donald Trump, and the "fiscal hawks" whose strident calls for action to contain the trillions of dollars in US government debt have either lost their influence, or are keeping quiet.

The latest sign of this shift away from fiscal discipline was on full display in the White House budget proposal released last week that abandons Trump's deficit cutting promises and relies on economic growth assumptions most economists dismiss as unrealistic to pay down the debt.

Though the budget proposal is unlikely to ever be implemented as Trump fights for re-election in November against Democrats who have their own radically different spending priorities, analysts worry that there is no will in Washington to address debt and deficit.

The Congressional Budget Office predicts the deficit will surpass $1 trillion and government debt will reach 81 percent of GDP by the end of September.

Economists warn those swelling levels are increasingly risky and could leave the US unprepared to fight the next recession.

"Ultimately, interest (on the debt) could become the largest federal government program," warned Marc Goldwein of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

"Your debt cannot rise faster than the economy forever."

- 'Tidal wave of debt' -

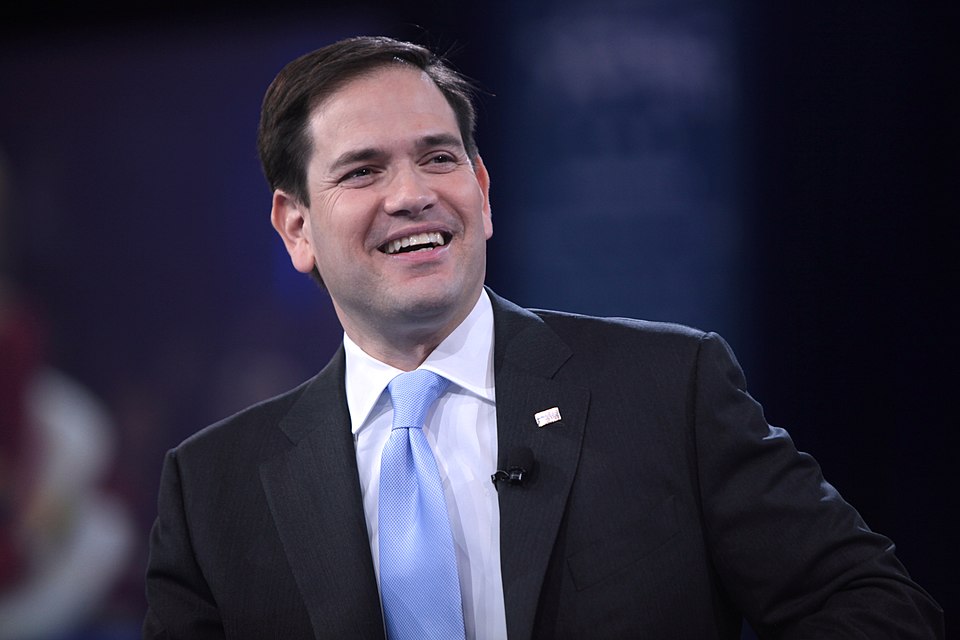

While they have remained silent under Trump, Republicans repeatedly hammered former Democratic president Barack Obama at every turn, from his plan to stimulate the economy out of recession in 2009 to his reform of the health care system.

Former House Speaker Paul Ryan, one of Obama's most prominent opponents in Congress, once warned the president's fiscal policies would unleash a "red tidal wave of debt."

Republicans blocked Obama's attempt to stimulate infrastructure spending, and put the debt clock front and center at their national convention ahead of the 2012 election, where voters ended up giving Obama a second term.

Trump's ascendance in 2017 appeared to spur a change of heart among those same lawmakers, who agreed to a massive tax cut for corporations and the richest Americans that has been credited with boosting growth but also piling on government debt.

"The fiscal hawks that were the loudest and most vocal during the Obama administration have been largely silent," said Romina Boccia of Heritage Foundation, a conservative Washington think-tank.

The Republicans once most concerned with the budget now have trouble "squaring their support for the (tax reform) with cuts to the deficit."

- Sending signals -

Trump's $4.8 trillion budget proposal does address the deficit, but abandons his pledge to eliminate the budget gap in 10 years, pushing the goal back to 2035.

And even the extended deadline achieves balance by projecting the US economy will grow by around 3.0 percent annually for years to come -- a feat almost unheard of.

The spending blueprint has no chance of getting through Congress unaltered, and Democratic and Republican lawmakers are seen as unlikely to take up a budget during election season.

But Ben Ritz of the left-leaning Progressive Policy Institute said the cavalier attitude towards spending betrays "political opportunism" by Republicans who wielded the debt and deficit as a cudgel against Obama.

"We're seeing these people who criticized Obama for much lower debt levels suddenly being ok with much higher levels under President Trump," he said.

- Who cares? -

And Trump himself has shown pronounced disregard for the future consequences of running debts so high.

On the campaign trail in 2016, he called himself "the king of debt." In January, The Washington Post reported Trump quipping in a behind-closed-doors speech, "Who the hell cares about the budget?"

Yet the record-long US economic expansion has to end sometime, and in testimony to Congress this month, Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell once again called for a "more sustainable budget."

With the key lending rate holding at a very low 1.5-1.75 percent, the central bank doesn't have much space to maneuver should a downturn hit.

And with a growing deficit and debt, the government has little room to boost spending to support a slowing economy.

Financed by the sale of US government bonds, that could be the force that brings the economic expansion to a halt, Goldwein said.

"I think there's kind of a slow-burn consequence," he said. "The more bonds we keep selling, the less investment there's going to be in the private sector. Over time, that's going to slow growth."